Category: Veronica

Veronica – ROM Board

ROM board with built-in EEPROM programmer.

It seemed so simple. The best ideas always do. However, sometimes the smallest problems end up taking the most time to solve. There was some swearing, I won’t lie.

You see, I had a really swell circuit that could take a ROM image and dump it into an SRAM. Since parallel EEPROMs exist that are accessed just like SRAMs, I figured I could just buy one, drop it in, and presto- ROM for Veronica. Flawless plan, right?

Well, a hundred hours or so later, it turns out the plan was in fact pretty darn solid, but the parts were against me. To recap, I designed a board for Veronica that would hold an EEPROM chip, and had a built-in ATTiny that acted as an interface between the EEPROM and my USBTinyISP programmer. Since EEPROM programmers are very expensive, this was a way to leverage the tools I had to program the ROM that Veronica needs to boot up.

So after getting the circuit working perfectly with an SRAM, I plugged in my shiny new EEPROM and tested it out. No worky. Figuring it was something silly, I started tracing things, double-checking connections, probing, the usual stuff. Everything seemed fine. Out came the logic analyzer to check the signals. Everything seemed fine. The EEPROM just refused to accept write commands, no matter what I did. I started simplifying the circuit further and further, until it was nothing except a hard-wired address and data byte, along with a button to trigger the write. No good. Nothing. Nada. Zip. Bytes would not write. I poured over the data sheets, thinking I must have missed some detail. I Became One with the timing diagrams. I googled. And googled. And googled. I googled until my fingers bled, I tell you! I posted desperate pleas on electronics forums. I circled around and around, checking wires, probing, logic analyzing, googling, ad nauseum. I had four EEPROM chips in the batch I bought, and ran every test on every one of them. None would cooperate. I built a special a circuit to disable the Software Protection Mode, even though it is supposed to be disabled by default. I tried everything reasonable, and a lot of very unreasonable things (which I will not go into here).

After many late nights of this, I was left with only one possibility. As Sherlock Holmes said, “once you eliminate the impossible, whatever remains, no matter how improbable, must be the truth”. Yes, all four of my chips were bad. I’d been discounting this possibility from the beginning, because it seemed incredibly unlikely. Nevertheless, I had to test this hypothesis once all others had been exhausted. I ordered two more chips from a different supplier. They worked perfectly, first try. Well, shit.

So here we are, after days of blood and sweat lost to a non-problem. I’d like to give a shout out to Jameco for being really cool about taking the chips back. I’d also like to thank the fine folks at the 6502, EEVBlog, and Hack A Day forums, who all provided helpful advice and a shoulder to cry on.

Okay, enough pontificating. Let’s get back to work. With the Real McCoy EEPROM now working in the programmer circuit, I was nearly ready to make the ROM board. A few loose ends needed to be tied up on the CPU board first. Remember how I had removed the tri-state buffer from the data lines, because it was causing problems, and didn’t seem necessary? Well, it turns out I do need it after all, because in order to program the EEPROM while it’s on the system bus, I need to be able to cut off the CPU board completely.

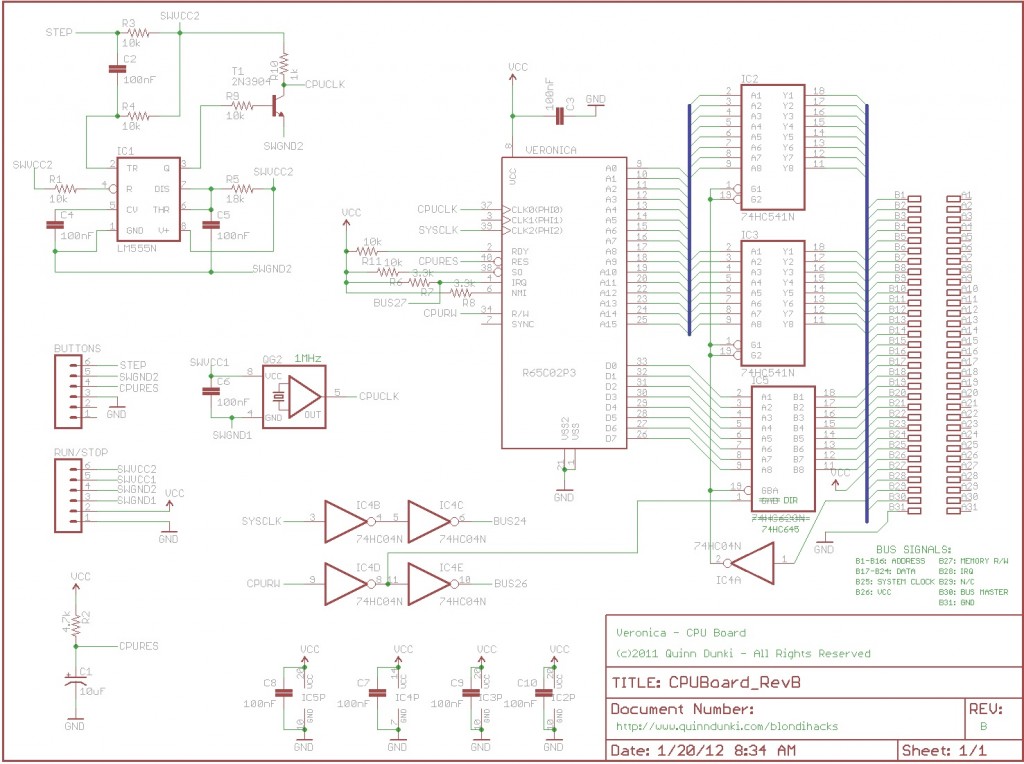

Thanks to a commenter’s tip (thanks KenS!), I picked up a 74HC645 bi-directional buffer to put on the data lines from the CPU. Amazingly, it has a nearly identical pin layout to the 74HC541 I was using, with one exception. It has a “direction” pin which controls which way data is moving through the buffer. I just need to hook that into the R/W signal on the CPU, which tells me whether it wants data going in or out at the moment. Wouldn’t you know, though, the sign of the Direction signal is opposite of the R/W signal. Luckily, since I used double-inverters to buffer my CPU signals, I happen to have an inverted version of that signal available on the board. Huzzah! While I was in there, I fixed another problem which the commenters caught (thanks John Honniball & KenS!). I had left the RDY input floating on the 65C02. Luckily, according to the datasheet, this is actually okay on the CMOS version. Still, it’s bad practice, and why ask for trouble?

Here’s the updated CPU board schematic (and eagle file):

One new bi-directional buffer, and a little tap running over to the inverted R/W signal to control it. Also, a shiny new pull-up on the previously dangling RDY line.

These changes were hardly enough to warrant a new PCB. The new buffer chip went right in the old socket where the incorrect buffer was before. Then I just needed to cut one trace and add a jumper to control it.

This extreme hack closeup is brought to you by Olloclip, the awesome triple-lens attachment for iPhone 4 and iPhone 4S. Yes, the inventor is my friend and this is a shameless plug. Accept it.

One last little detail- I need a way to pull the Bus Master signal low on the CPU board so it will be denied access to the bus during EEPROM programming. One of these days, I’ll get around to building a bus arbitration circuit that handles all this, but until then:

Laugh all you want, but it’s a considerable step up in sophistication from my previous method. It’s even labelled! This is professional grade stuff, people. We don’t mess around here at Blondihacks.

Okay, the CPU board is in better shape. Next, I wanted to make really sure everything worked before building the permanent ROM Board, so I ran through a full code iteration cycle using the breadboard circuit. This is similar to the test I ran with the SRAM, except everything is hooked up for real- the clock line, the address decode circuit, everything. Here you can see me power up, and the CPU starts running an infinite loop at $FE00 in the EEPROM. Then I flip to program mode, run the programmer on the laptop to move the code to $FE10 in the EEPROM, flip back to run mode, and reset Veronica. She then starts running the new code:

If you look closely, you’ll also see some probes being used as jumpers on the CPU board. Those are my tests of the above hacks to the CPU board. I wasn’t taking any chances and tested the hell out of everything.

Okay, now to the fun part- building the board! Here’s the latest version of the ROM board schematic (and eagle file), complete with Atmel EEPROM. Note that I’ve given up on my previously stated ability to write an SRAM with this circuit. The SRAM is a different socket width, and the pins are all shuffled from the EEPROM, so handling both was more trouble and board space than it was worth.

One thing to note, the write process has changed from being CE-driven to WE-driven. This was recommended by the data sheet, and allows something cool, which we'll see shortly.

Let’s segue into software for a second. Since last time, I’ve made improvements to the EEPROM programming code that runs on the ATTiny. First of all, EEPROMs have some slightly different timing requirements than SRAMs for writing. Second of all, writing to an EEPROM is very slow, normally. Around 5ms per byte, in fact. That’s brutal and would be really bad for iteration time. As any software person knows, minimizing iteration time on development is critical. Fortunately, this EEPROM has a special feature called Page Write Mode that lets you write 64 bytes at a time. The trick is that it is very sensitive to timing. So sensitive, in fact, that my old code couldn’t handle it. Subsequent bytes need to be written within 150µs in page-write mode and my very sloppy code could only manage about 180μs. This new version manages 50µs comfortably. Of course, I could write it in assembly and get it much faster still, but there’s no need. It’s now writing to the EEPROM as fast as the chip will allow in any case. The only other tweak needed is that Page Write mode requires WE-driven writing. Single-byte mode is more like an SRAM, whereby you can trigger writes with either WE or CE. The above schematic reflects this change. Getting Page Write mode to work was tricky, but well worth it. A speed increase of nearly 64x is nothing to sneeze at! Surprisingly, some of the high-dollar commercial programmers don’t even support this. Nutty.

Here’s the new code:

Okay, now on to the PCB! Here’s the board layout (and eagle file):

Making these things is way more fun than it should be. It's like those puzzles where you have to untangle all the strings without disconnecting anything.

I’ve made a number of refinements to my PCB-making process. It’s improved to the point that I can pull off shameless stunts like putting my logo in the copper:

Shameless plug is shameless. And yes, I borked up one of the drill holes big time. Otherwise, I'm quite chuffed with how this board turned out.

I’m considering writing a follow-up to my original PCB article that includes all my improvements. If this is something you’d be interested in, let me know in the comments.

PCBs are surprisingly difficult to photograph. Any amount of direct light makes crazy glare and hotspots. This is all indirect light, but the result is grainy because there isn't enough.

Here come the obligatory build progress photos. Riveting!

Ground jumpers, VCC distribution, and signal jumpers. Also random other stuff. This assembly was an exercise in figuring out what was going to interfere with what so that things got installed in the correct order.

Address and data jumpers. Not even a two-layer board would have saved me here. We're in four-layer territory now.

I SAID LOOK AT IT. Wait... don't look too closely, or you'll see things like the two traces I mangled with the drill, the Vcc trace that I put in the wrong Eagle layer, and other unseemly things.

Okay, now that the “Look what I did mommy” ego trip is out of the way, let’s do a real test. Here’s the same code-relocation test I did before, but on the real board. You can see my USBTinyISP plugged in to the back of the ROM board, and of course HexOut is lighting the way. Again, I’m running code at $FE00, using the programmer to write a different ROM image at $FE10, then running that. All without powering down or even stopping the CPU. Gangbusters.

That’s all for now. Thanks again to all the commenters for their great feedback and kind words. Cheers!