Category: Veronica

Veronica – EEPROM Programmer

An onboard way to program an EEPROM, or fake one.

Well, now that Veronica is up and running in real hardware form, she needs some real ROM to play with. That means I need a way to burn an EPROM (UV-erasable) or flash an EEPROM (electrically-erasable). The latter seems easier to use, but the programmers for them are very expensive. So what’s a girl to do? Well, I may not have an EEPROM programmer, but I do have the excellent (and cheap!) USBTinyISP in-circuit programmer for AVR microcontrollers. Can I leverage its abilities to program an EEPROM? I bet I can…

The basic idea is that I will use the USBTinyISP to dump my ROM image into the flash memory of an AVR, then run code on the AVR to copy that data into my EEPROM. Sounds just crazy enough to work. Crazy like a fox. Like a fox in the henhouse. Like a chicken with its head cut off. Okay, that metaphor kinda got away from me there, but you get the idea.

This project started as a way to dump some data into an SRAM for the CPU to use during startup, so I wouldn’t have to key it in with the dead-start panel. Then I read up on EEPROMs and learned that they work pretty much the same way as SRAMs, so the same circuit could work as a standalone EEPROM programmer! Well, then it occurred to me that I might as well do all of the above! So, this project is a card for Veronica that can do three things:

- Burn an EEPROM all by itself, for insertion into any device

- When inserted into Veronica, burn an EEPROM prior to startup for the CPU to use directly

- When inserted into Veronica, fill an SRAM chip with data that will look like ROM to the CPU

The nicest part of this approach is that I can leave the EEPROM installed. With an external programmer, I’d have to keep transferring the chip back and forth from the programmer to Veronica. My background is in software, and one thing I’ve learned is that the early days of a project is when the most iteration is needed. When I get down to programming this ROM code, I expect to need to reflash it a lot.

Before I could do anything related to ROM, I was going to need a memory map of sorts for Veronica. It’s very early yet, but so far I’ve got this:

- $0000..$00ff: Reserved for special code needing 6502 zero-page addressing

- $0100..$01ff: 6502 stack

- $0200..$edff: Program memory

- $ee00..$fdff: Reserved for special stuff. Probably I/O buffers, soft-switches, memory-mapped device control, etc.

- $fe00..$fff9: System ROM

- $fffa..$ffff: 6502 reserved vectors (NMI, Restart, IRQ)

So, it’s roughly 48k of program space, 12k of ROM, and 4k of “to be determined”. 12k of ROM seems like rather a lot, so that may shrink. It’ll do as a ballpark for now, though.

The trick then, is that I need an AVR microcontroller that can hold my entire ROM image. I also want it to be a one of the really small ones, since I don’t want to use a lot of board space or power for this. I compromised on the ATTiny85, which is the awesome 8-pin form factor that I like, and has 8k of flash onboard. That will mostly fill my ROM. I’ll probably reclaim the leftover 4k for program memory, or I could program the ROM in two phases. We’ll see.

I use three 8-bit shift registers to interface the ATTiny with the memory chip. I fill the memory chip one byte at a time, by serially pushing two address bytes and a data byte out of the ATTiny. It has just enough pins left over to manage the memory chip’s control signals. The address and data registers share a clock, so that means the data byte actually gets pushed out twice, since there are two address bytes. That’s harmless though, and it saves me a pin on the ATTiny. I’m also using the old trick of connecting together the shift clock and latch clock on the registers. That saves another pin on my ATTiny, and is easily compensated for in software (since it puts the latches one pulse behind).

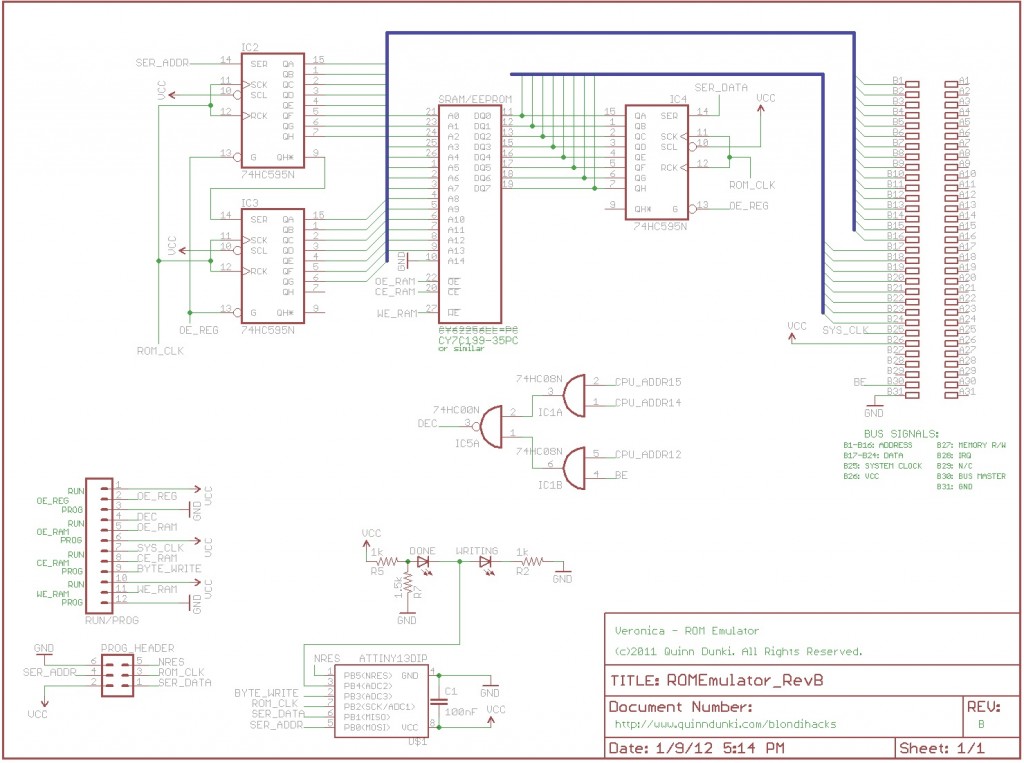

Here’s the schematic. The Eagle file is also available.

Here you can see the big memory chip (SRAM or EEPROM), surrounded by the shift registers. Below that is a set of logic gates to activate the ROM whenever the CPU accesses the upper 12k of the address space. At the bottom is the ATTiny, which pushes data out to the memory chip when so requested. Note that the Bus Master signal can be used to completely disable the ROM. This could be useful someday if two other cards on the backplane want to talk directly to each other. There are two LEDs- a red one to indicate that EEPROM programming is underway, and a green one for when it is done. The big header on the left is for a toggle switch which selects Run or Program mode. In Run mode, the CPU is using the ROM normally. In Program mode, the ATTiny is doing its thing.

It’s quite simple in principle, but getting it to work turned out to be a real adventure. I started on the breadboard with just the core of the design. I left out the address decoding, bus control signals, and so forth.

So far so good, right? I'm using a 32k SRAM here to stand in for the EEPROM. At the top is the ATTiny, and the three shift registers.

For initial testing, the ATTiny was configured to simply fill the memory with $42. In addition to the circuit shown above, I also hooked up my hex input panel and HexOut to the SRAM. This would allow me to inspect the contents of the chip after the microcontroller was done, and see if it worked.

Well… it didn’t. The memory was filled with mostly junk, along with some scattered $42s. I started by trying to isolate the problem using software (my first instinct, given my background). I made a bunch of special versions of the ATTiny code to test various theories about what might be wrong. I couldn’t seem to learn anything new this way. No matter what I did, the memory was filled with junk. The thing was, though, if I inspected memory right at power up, then again after running the microcontroller, the memory contents had changed! So something was being written, just not the right thing.

Since there were some scattered $42s in there, I figured this might be a timing problem. I’m strobing the Chip Enable line on the SRAM to write the data at nearly the same moment as the shift registers are finishing. I knew during design that this might be a problem for the SRAM to get the data reliably, and perhaps my fears were realized. Having exhausted the software diagnostics, it was time to break out the logic analyzer. I say that with mixed feelings. When I need the LA, it means things aren’t going well. However, it also happens to be my favorite toy ever. I wish it were a person so I could marry it.

So, my current theory was that the data wasn’t being reliably presented on the SRAM’s inputs at the time the Write signal is received. So I probed up the data pins and the Write pulse to test that theory:

D0-D7 are the data lines, and D10 is the Write pulse. The cascading effect that you see on D0-D7 is the bits being shifted serially into the register. You can see that the data lines have my test value of $42 nearly a full microsecond before the write pulse, and they hold the value until well after. I verified this across the first 20 or so pulses, which proved that the data writing sequence was solid. No problem here.

Okay, so the right data is there at the right time, so maybe the addresses are wrong. Perhaps the addresses aren’t counting up sequentially, or aren’t presenting reliably for the SRAM. Time to probe those:

Same setup, but now I'm probing the lower eight bits of the address. D10 is the Write pulse, and as before, you can see the address bits getting shifted in. This Write pulse is the 16th one, and you can see that address 0x0010 is being correctly presented comfortably ahead of the write operation. No problem here either.

You might look at all that data and conclude that, in fact, nothing is wrong. You may say that this circuit really looks like it’s working. That’s because it is. Yes, friends, after a few long hours of debugging, I determined that in fact it works perfectly. The problem turned out to be my tools. I was leaving my hex input panel and my HexOut display connected while running the programming operation. The former was creating contention on the address lines of the SRAM, and the latter was making some noise on the data lines. It was my own home-brew tools that were creating the problem. I believe Jean-Luc can express this feeling better than me:

With that sorted, I was able to get 100% reliable results by running the programmer, then plugging in my tools after it was done. Presto, memory full of $42s!

In this photo you can also see the address decode logic on the right. I wanted to test everything before connecting it to Veronica. The big toggle switch (4PDT!) manipulates all the control signals of the memory chip to switch it between being programmed by the ATTiny, or being used in normal operation by the CPU. In the latter mode, it is also safe to hook up my hex input panel and HexOut display.

The big remaining task was coding the ATTiny to handle a full ROM image. I’m starting with a 512 byte image, because I prototyped this with an ATTiny13a, which only has 1k of flash. A couple of hundred bytes are lost to the code used to transfer the data to the memory chip, so 512 bytes is a good test case. The ATTiny85 is a drop-in replacement that will hold 8k, almost my entire ROM image. Until Veronica can actually do something, 512 bytes of ROM is plenty in any case.

Here’s the ATTiny13a version of the code:

The test ROM image I’m using so far just has an infinite loop at the very start. This image is loaded into the top 512 bytes of the memory chip, and also includes the reserved vectors. Note that the restart vector is pointing to the bottom of the ROM image, where our test code conveniently lives. The data “0x4C,0x00,0xFE” is a hand-assembly of this 6502 code:

$FE00: JMP $FE00

Note the ROM image is a global C array. This is an easy way to make the linker put it in the code segment, which means it ends up in the big flash space of the ATTiny, as opposed to the really small RAM or EEPROM areas. To access this flash memory data, I’m using the special avr-gcc macros PROGMEM and pgm_read_byte, which allow you to read data out of flash memory without copying it all into onboard RAM (where it wouldn’t fit). The C language isn’t really designed for the Harvard Architecture used by AVRs, so sometimes a little trickery is needed to get it to play nice.

Now we’re cooking with gas. It’s time for an all-up test. Here’s the breadboarded unit connected to Veronica’s bus. The CPU is kept off the bus during programming, and when the ATTiny done, I manually re-enable the CPU and reset it. If all goes well, the address lines should be showing a tight infinite loop at addresses $fe00, $fe01, and $fe02.

Huzzah! No video this time, but trust me, that last blurry digit on HexOut is whipping around in our little infinite loop, just as it should.

Awesomesauce. Now we just need to build the PCB for this, and give it a real EEPROM to play with. Soon Veronica will be running code in a completely standalone fashion, just by turning her on (if you know what I mean). She’ll be a real computer soon!

This might seem like a long writeup for just a handful of chips on a breadboard, but the real lesson here was the debugging process. Also, be careful about building your own diagnostic tools unless you really know what you’re doing. 🙂 I’d love to know why HexOut spits out so much noise on the data lines. If you have any advice, share it in the comments below!